From Beringia to the Vikings: Ancient Journeys Through Ice and Adaptation

In the vast tapestry of human history, few stories captivate like those of populations who thrived in the planet's harshest cold environments. The Beringian standstill—a pivotal chapter in the peopling of the Americas—and the rise of the Vikings in Scandinavia offer fascinating parallels and contrasts. Both groups navigated extreme climates, evolving unique adaptations that shaped their genomes, bodies, and cultures. Yet, their paths diverged dramatically: one led to the Arctic indigenous peoples like the Inuit, while the other forged the Norse seafarers who raided and settled across Europe.

This article delves into the histories, daily lives, climatic challenges, and genomic legacies of these groups. Drawing from archaeological, genetic, and paleoclimatic evidence, we'll explore how isolation in icy refugia molded human resilience—and what echoes remain today. Note: While some popular notions link European haplogroups like H to Beringia, genetics tells a different story; Beringian migrants carried distinct lineages, highlighting separate evolutionary trajectories.

The Beringian Standstill: A Frozen Pause in Human Migration

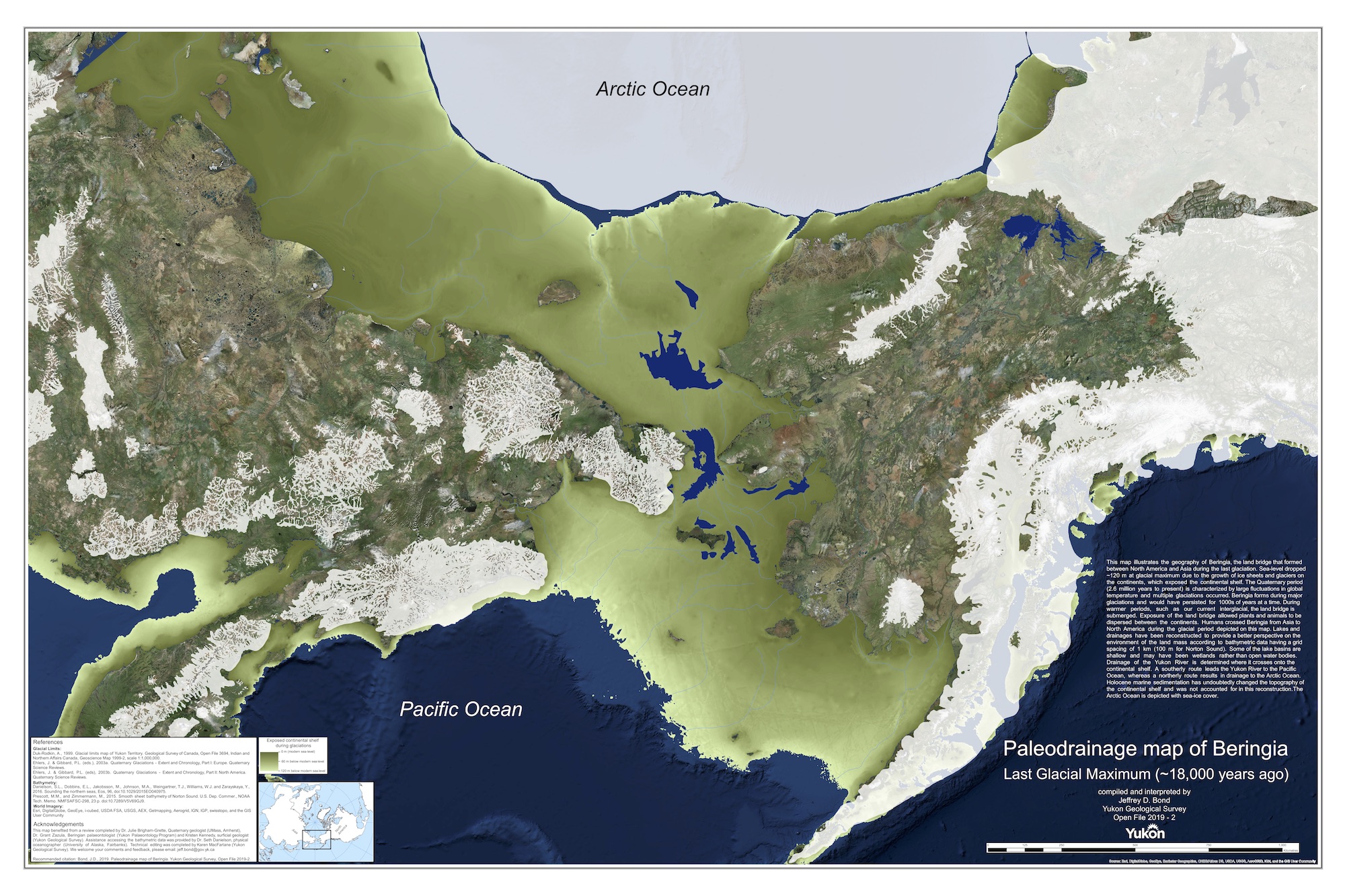

Around 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a group of ancient Siberians became isolated on the now-submerged land bridge known as Beringia. This vast region, stretching from eastern Siberia to western Alaska, was an ice-free refugium amid global glaciation. The "standstill" hypothesis posits that these migrants were stranded for 2,400 to 9,000 years (not 11,000 as sometimes overstated), due to massive ice sheets blocking southward paths into the Americas.

Beringia wasn't a barren wasteland but a steppe-tundra ecosystem supporting megafauna like woolly mammoths, horses, and bison. Paleoecological records show a cold, arid landscape with sparse vegetation, high winds, and low precipitation—winters dipping to -20°C or lower, with brief summers around 4°C cooler than today. Humans here were hunter-gatherers, relying on big-game hunting, fishing, and gathering hardy plants. Tools like microblades and bone artifacts from sites like Swan Point in Alaska reveal sophisticated survival tech, including insulated clothing from animal hides.

This isolation fostered genetic divergence. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups A, B, C, D, and X (particularly X2a) dominated, originating from East Asian founders—no trace of European-linked haplogroup H or its subclade H2a, which arose later in the Near East and Europe. Post-standstill, around 15,000 years ago, warming climates opened ice-free corridors, allowing migration into the Americas and the eventual emergence of diverse indigenous cultures, including the Thule ancestors of the Inuit.

Viking Origins: From Post-Glacial Pioneers to Norse Raiders

In contrast, Scandinavia's human history began as the LGM ice sheets retreated around 12,000–11,000 BCE. Early settlers were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from southern European refugia (Western Hunter-Gatherers) and eastern Baltic regions (Eastern Hunter-Gatherers), arriving via land routes through modern Denmark and Germany. By 7,000 BCE, stable communities thrived, hunting reindeer and seals in a thawing landscape.

The Neolithic era (~4,000 BCE) brought Anatolian-derived farmers, introducing agriculture and mixing with locals. A major influx came around 2,800–2,000 BCE with Indo-European steppe herders (Yamnaya culture) from the Pontic-Caspian region, carrying R1a and R1b Y-chromosomes and Proto-Germanic languages. This genetic cocktail—~40-50% hunter-gatherer, 30-40% farmer, 20-30% steppe—formed the Nordic Bronze Age, evolving into Iron Age Germanic tribes.

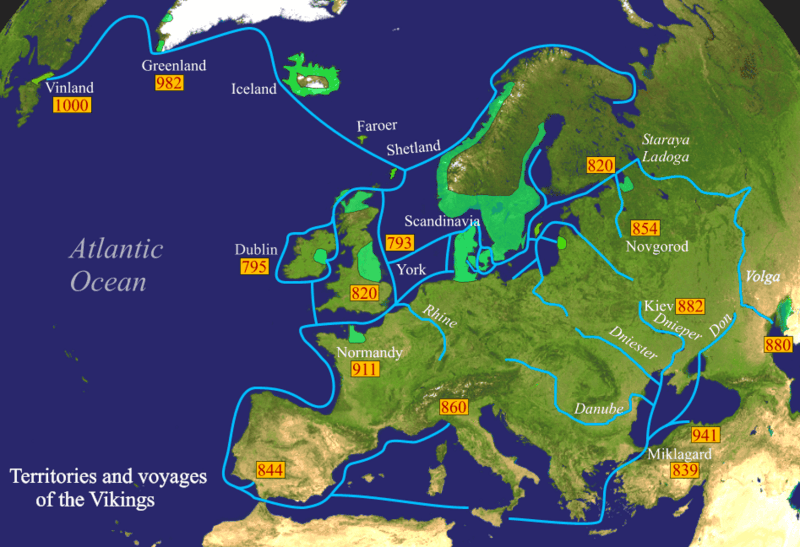

The Viking Age (793–1066 CE) emerged from overpopulation, climatic shifts, and technological advances like longships. Vikings weren't a unified people but Norse farmers, traders, and warriors from Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, expanding to Iceland, Greenland, and beyond. Haplogroup H, peaking at 40-50% in Scandinavians, reflects this European heritage, with no Beringian ties.

Climate Showdown: Beringia's Extremes vs. Scandinavia's Temperate Edge

During the LGM, Beringia was a cold, dry steppe-tundra, with July temperatures ~4°C cooler and January ~2°C cooler than modern equivalents—overall harsher than habitable European zones. Scandinavia itself was largely ice-covered, forcing humans to southern refugia like Iberia, where winters were milder (4-8°C cooler) with more precipitation and diverse resources.

Post-LGM, Europe warmed rapidly, fostering forests and agriculture by 10,000 BCE. Beringia remained Arctic-like, with persistent cold driving adaptations in its descendants. Viking-era Scandinavia experienced the Medieval Warm Period (~900–1300 CE), aiding expansion, but winters were still brutal—sea ice trapped ships, and storms delayed voyages. Beringia's isolation amplified selection pressures, while Scandinavia's connectivity allowed cultural exchanges.

Daily Life: Survival in the Deep Freeze

Beringian life revolved around mobility: hunting megafauna with atlatls, fishing in icy rivers, and sheltering in semi-subterranean dwellings insulated with sod and bones. Diets were high in protein and fat from seals and caribou, with minimal carbs—essential for thermogenesis in -20°C winters.

Vikings, in a more temperate yet variable climate, farmed barley and rye in short summers, herded sheep and cattle, and fished cod. Winters meant indoor activities: storytelling, crafting, and feasting on preserved foods like butter-laden porridge. High-fat dairy and meat diets (35-40% fat) fueled them through dark months, with no evidence of widespread heart disease due to intense activity and short lifespans (30-40 years). Social adaptations included communal longhouses for warmth and Viking raids for resources during harsh years.

Genomic and Physical Adaptations: Evolving for the Cold

Beringian descendants, like the Inuit, exhibit profound cold adaptations per Bergmann's and Allen's rules: shorter limbs, broader chests/torsos to minimize heat loss, and flatter facial features (including potentially smaller breasts) to reduce frostbite risk. Visceral fat storage around organs provides insulation and energy, enabled by genes like CPT1A for efficient fat metabolism on marine diets rich in omega-3s. These mutations lower LDL cholesterol and insulin, aiding survival but raising modern risks like diabetes with Western diets.

Scandinavians show milder adaptations: stockier builds and pale skin for vitamin D synthesis in low sun, but more external fat storage (e.g., in hips and breasts) due to calorie surpluses from farming. Haplogroup H may link to metabolic efficiency, but Vikings relied more on cultural tools—wool clothing, skis, and ships—than genetic extremes. Larger breasts in some European women tie to estrogen and nutrition, not cold selection.

Aftermath: Legacies in a Warming World

Beringian migrants populated the Americas, their adaptations persisting in Inuit genomes, now challenged by climate change—melting ice disrupts hunting, while dietary shifts amplify health issues. Vikings' expansions faded with the Little Ice Age (~1300 CE), but their genes influence modern Scandinavians, who face fewer cold extremes thanks to technology.

These stories remind us: Human adaptation is dynamic. As global warming reshapes the Arctic, understanding these ancient resiliences could inform future survival strategies.

What do you think—could Viking butter feasts or Inuit fat-metabolism genes inspire modern diets?